About

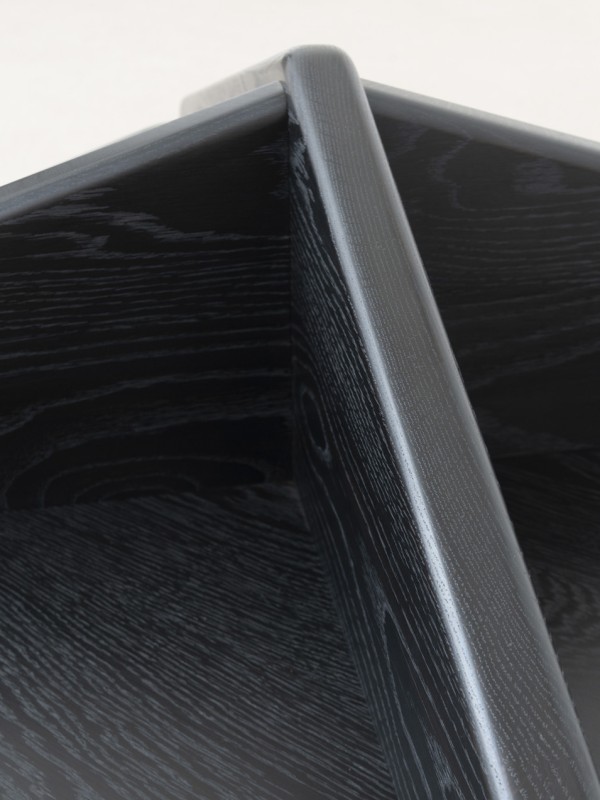

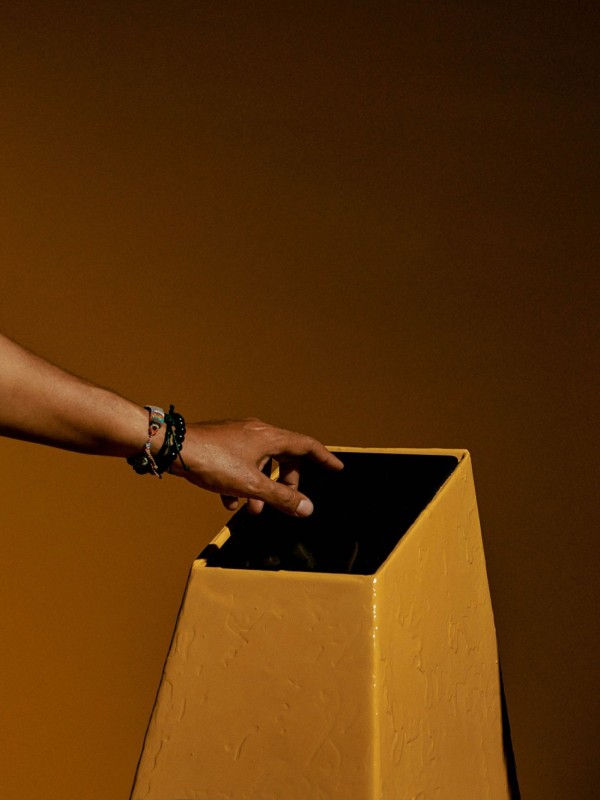

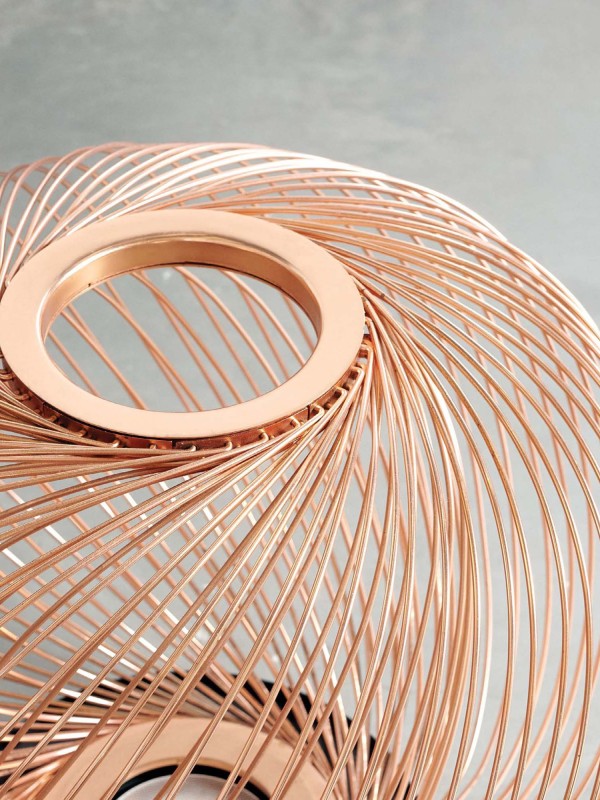

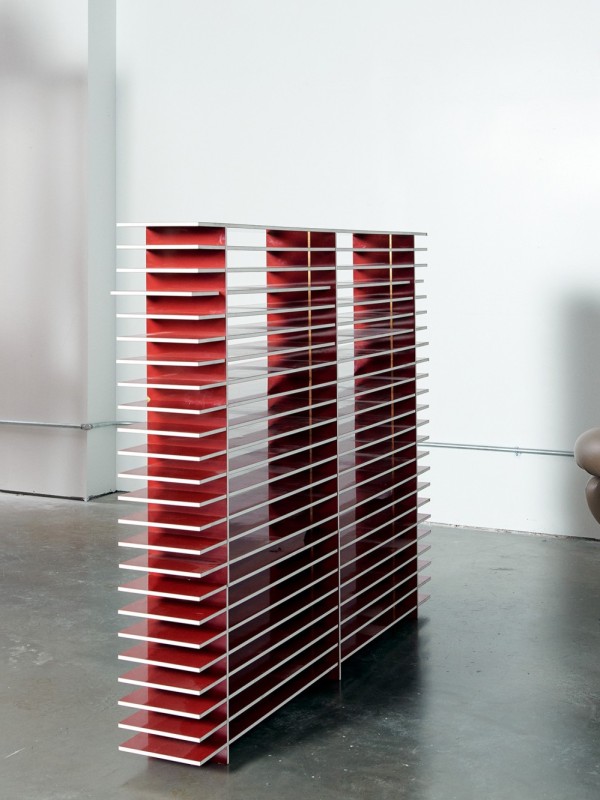

Stephen Burks Man Made is a hands-on collaborative design studio deeply invested in the transformative power of craft techniques that challenge the limits of new technologies within industrial production.

We believe in a pluralistic vision of design that is inclusive of all cultural perspectives and backgrounds.

We bring the hand to industry through a community-driven, workshop-based practice.

Our projects include furniture, lighting, interiors, exhibitions, and product design.

We are Stephen Burks (Principal), Malika Leiper (Cultural Director), Vara Yang (Design Consultant), and Fridolin Jeger (Design Assistant).

Our solo exhibition Stephen Burks: Shelter in Place, formerly at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta (September 16, 2022 - March 5, 2023) is part acclaimed mid-career survey and part commissioned speculative project presenting the last decade of professional practice alongside new expressions of radical domesticity through handcrafted industrial design.

Most recently, Stephen Burks: Spirit Houses opened at Volume Gallery in Chicago and Stephen Burks: Shelter in Place (November 19. 2023 - April 16, 2024) opened at the Philadelphia Museum of Art where Stephen became the first African American to receive the Collab Design Excellence Award.

Follow us on Instagram @stephenburksmanmade and contact us at info@stephenburksmanmade.com.

Stephen Burks

Chicago native, Stephen Burks is an industrial designer, product development consultant, and educator whose innovative approach to design synthesizes craft, community, and industry. Independently and through association with various non-profits, he has collaborated with artisans and craftspeople in over ten countries on six continents. His socially engaged practice seeks to broaden the limits of design consciousness by challenging who benefits from and participates in contemporary design.

Stephen and his studio, Stephen Burks Man Made, have been commissioned by many of the world’s leading design-driven brands to develop collections that engage hand production as a strategy for innovation to express a more pluralistic vision of design including BD Barcelona, Cappellini, Dedon, MASS Design Group, Missoni, & Roche Bobois.

He has had solo exhibitions and led curatorial projects at the Studio Museum in Harlem (Stephen Burks Man Made, 2011), the Museum of Art & Design (Stephen Burks, Are You a Hybrid, 2011), and the High Museum of Art (Stephen Burks: Shelter in Place, 2022).

He has been visiting faculty and a strategic consultant to academic institutions around the globe and taught architecture and design at Berea College, Columbia University GSAPP, ECAL, the University of Arkansas Fay Jones School of Architecture & Design, and the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Stephen is the only African-American to win the Smithsonian Cooper Hewitt National Design Award in Product Design and the only industrial designer to be awarded the prestigious Loeb Fellowship at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Malika Leiper

Originally from Cambodia, Malika Leiper is interested in the culture of design across various disciplines with a particular focus on emergent contexts in Southeast Asia.

After completing her master’s in urban planning at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, she consulted with restaurants, non-profits, local governments, and museums on research and strategies to build creative cultural capacity, often through public programming and community engagement.

She approaches design as a collaborative process of translating knowledge and insights from different worlds into one common language through technical, moral and utopian applications.

Most recently, Malika has contributed to Disegno Journal #34 as a Het Nieuwe Instituut inaugural emerging writing fellow with her first published short story, When The Words Don't Exist.

Vara Yang

Vara Yang joined Stephen Burks Man Made as an industrial designer in New York in 2017.

Before working at Stephen Burks Man Made, she worked with several startups helping them bring their products and services to the market, including smart home devices, smartwatches, smart jewelry, and 3D printers.

Now an independent consultant based in Rotterdam, she continues to work with the studio on projects at various scales from furniture design to packaging to exhibitions.

Vara received her bachelor’s in design engineering from National Cheng Kung University in Taiwan and her master’s in Industrial Design from the Rhode Island School of Design.

news

How Stephen Burks “Future-Proofs” Craft

Stephen Burks: Shelter in Place Book Review in Untapped Journal by Francesca Perry

In the spring of 2020, the American industrial designer Stephen Burks was, like many of us, confined to his home amid the Covid-19 lockdowns.

But while some people’s productivity amounted to a sourdough starter, Burks was inspired to draw, design, and make.

With his partner, the cultural strategist Malika Leiper, the Chicago-born, Brooklyn-based designer experimented with hands-on creating, unbounded by practical concerns.

Soon, this creativity morphed to respond to the evolving needs and experiences of domestic life. For our homes were in the process of transforming—as places, and as containers of suddenly a lot more life—and these new uses of interior realms called for new kinds of objects.

The body of work that emerged, called Shelter in Place, includes Supports, supersize stands for smartphones and tablets, and Private Seat, a cocoon-like, screened-off chair.

The creative process prompted conversations with Monica Obniski, curator of decorative art and design at Atlanta’s High Museum of Art, and resulted in the exhibition “Stephen Burks: Shelter in Place” (through March 5), as well as a book of the same title (Yale University Press), out last November.

The book speaks to a particular moment in time.

But while we might feel a long way from those early experiences of pandemic life, the ramifications are still being felt, and a key site of change has been the home.

Can Burks’s work point to ways of reshaping our domestic lives and landscapes for the better?

As an accompaniment to the exhibition—which surveys the last decade of the designer’s work, as well as his Shelter in Place project—the book is in part a catalog, but goes beyond this scope to critically and comprehensively dig into the context within which Burks’s practice is situated and the propositions his work puts forward.

It features seven texts, including an in-depth introduction by Obniski, a personal piece from Burks focusing on the creation of Shelter in Place, a short but sweet text from friend and fellow designer Patricia Urquiola, and essays by critics and curators Glenn Adamson and Beatrice Galilee.

Immersive images of Burks’s work, captured by photographers Caroline Tompkins and Justin Skeens, bring his creations powerfully into focus.

Of arguably greatest interest, though, are the book’s dialogues, presented as Q&As, which in their free-flowing format reflect the creative multiplicity of Burks’s work itself.

One is between Burks and Michelle Joan Wilkinson, a curator at the National Museum of African American History and Culture, who interviews him about his career.

The other is between Burks and the late legendary critic bell hooks, who discusses the designer’s work in its broader cultural context. (It’s one of hooks’s last published conversations before her passing.)

Burks—along with his practice, Stephen Burks Man Made—is known for craft-centric furniture designs, and the most compelling aspect of both the book and Burks’s work is what this approach says about the past and future of design.

His focus on participatory craft and the value of the hand speaks to an embrace of global diversity, design democracy, and cultural multiplicity, which implicitly and explicitly challenges the European canon of design and its traditional hierarchical division of labor, a subject carefully explored in Adamson’s chapter.

Burks has worked with artisans all over the world, from Senegal to Colombia, seeking to champion these communities and their craft traditions.

His core belief, he writes, is that “everyone is capable of design”—a powerful statement.

He is careful to avoid the extractive or appropriating behaviors that working with craftspeople risks—behaviors that have historically sought to profit from community labor, fetishize otherness, or both.

Obniski tells us that Burks aligns himself as a “collaborator instead of a colonizer,” and she positions craft—especially how Burks practices it—as “a way to connect to one another and, perhaps through collaborative endeavors, to create a more inclusive design system.”

Burks’s focus on collaborative craft emerged from an experience in 2005, when he was invited to South Africa by the nonprofit organization Aid To Artisans and the design brand Artecnica as part of a project pairing designers with artisan communities.

Burks worked with local craftspeople to develop commercially viable pieces of contemporary design using their traditional skills in unexpected ways, including chairs wrapped with leftover plastic from parade floats and furniture surfaced with shredded magazines.

After South Africa, Burks tells hooks, “my work quickly became about creating more space, opening doors, trying to take this kind of monoculture of European design and make it more pluralistic, more hybrid, which I think is the reality of the world.”

He has since worked extensively across Africa, Asia, and Latin America, as well as the United States, Europe, and Australia, on projects that center community craft traditions.

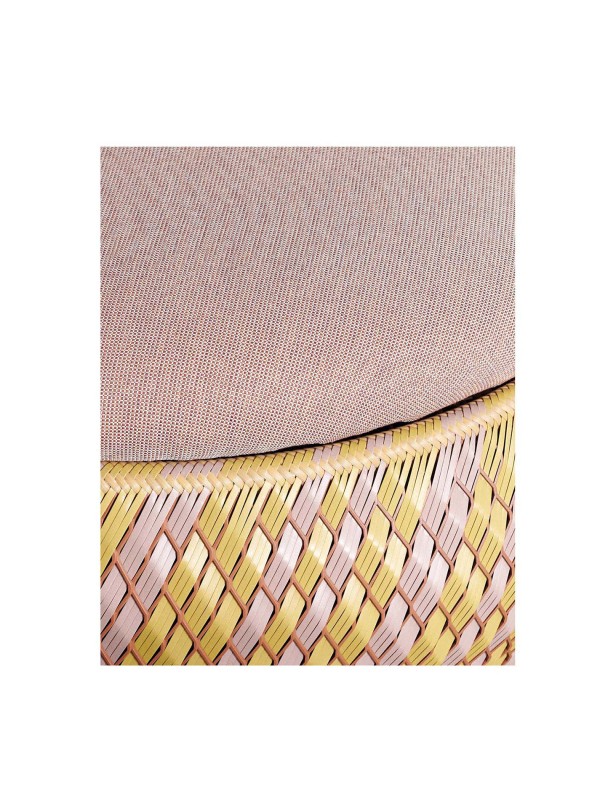

His Dala (2012–14), Kida (2020), and The Others (2017) ranges for the German furniture brand Dedon, for example, involved working closely with master weavers in the Philippines.

Through his work he hopes to embed this global cultural representation and diversification of design in our homes, creating functional objects as vehicles that propose a more inclusive future.

Nevertheless, as Burks’s commissions come primarily from luxury brands, his furniture is often only affordable to those with wealth, so while inclusivity underpins his practice, it does not define his audience.

These high-end consumers may be precisely the people that Burks wishes to influence—shifting perceptions of craft and elevating overlooked and diverse creativity—but it’s challenging to see just how much they would look beyond a beautiful product to learn about and be influenced by the way it was made.

Of course, not all Burks’s works are commercial pieces, and the very act of experimenting and prototyping is crucial for him.

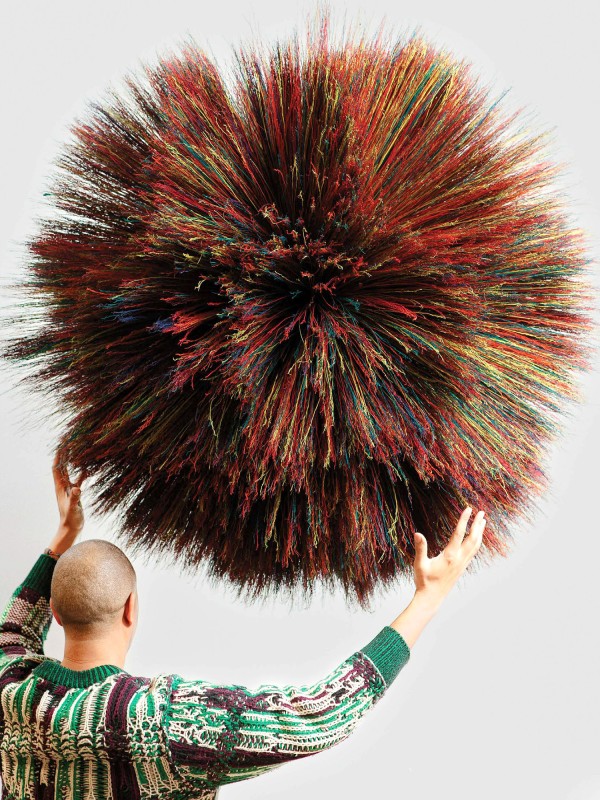

As part of his collaboration with the Student Craft initiative at Berea College in Kentucky, he produced Crafting Diversity (2020), a series of inventive home accessories, from throws to baskets and even a decorative broom.

Although made in partnership with the furniture company MillerKnoll, the items were not made for a consumer market, and instead seek to explore new expressions of traditional crafts such as weaving and woodworking.

This approach is a typical one for Burks: supporting, championing, and sustaining historic craft techniques—what Galilee refers to as “future-proofing” crafts—and reinterpreting them for contemporary life, harnessing design to mediate between yesterday and tomorrow.

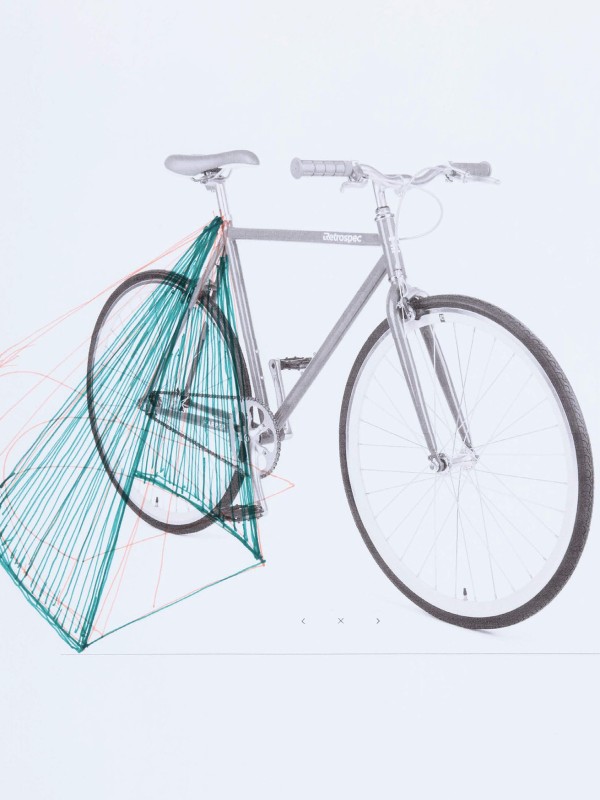

This can be seen in Woven TV, part of Shelter in Place, which blends physical craft with digital technology for the phygital generation.

Responding in part to the shrinking of the television’s domestic presence to a wafer-thin device, the prototype comprises a large industrial-metal mesh surround for a flat TV screen.

Although the initial design was, according to Burks, “an exercise in the structural integrity of weaving a cabinet,” the piece’s lattice enclosure invites users to decorate it with materials of their choice to personalize the structure.

The piece seems to respond to what Obniski outlines as the central question behind the Shelter in Place project—“How can we design our interiors to enable joyful living while empowering creativity?”—and reflects Burks’s desire for people to participate in designing their surroundings.

But it reveals a tension between ambition and use: a designer can certainly set an intention for how an object could or should be used, but ultimately the life of that object will be dictated by the user, who may not share those ambitions, or participate in the way the designer intended.

The idea of better living through design, with its origins in modernism, is a driving concern for Burks. In fact, the book positions the 20th-century design movement as underpinning his practice. One can understand why: Burks grew up in Chicago, a city shaped by modernism, and studied product design at the Illinois Institute of Technology’s (IIT) Institute of Design, which was originally founded as the New Bauhaus: Chicago School of Design by Bauhaus professor László Moholy-Nagy, in 1937.

Modernist architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe, who had a significant impact on Chicago’s urban landscape, designed IIT’s campus.

“I’ve always considered myself a modernist,” Burks tells Wilkinson, adding that modernism is a “critical rethinking of everything we knew.”

He even likens the goals of modernism to those of the “recently freed people of the African diaspora” from that time—to reinvent, break free, find new expressions, and create their own roles.

Obniski connects Burks’s practice to the way the Bauhaus school sought to elide divisions between different creative disciplines, and notes conceptual similarities between the work of Burks and Bauhaus textile artist Anni Albers, who saw craftspeople, industrial designers, and artists as one and the same.

Obniski also quotes part of architect Walter Gropius’s 1919 Bauhaus Manifesto—“Today the arts exist in isolation, from which they can be rescued only through the conscious, cooperative effort of all craftsmen”—positing that Burks’s practice internalizes this belief.

In part, she’s right. But Burks’s work seems to acknowledge that these ideals of inclusivity and pluralism were not comprehensively achieved through modernism.

With Wilkinson, he talks about the “conflict” of learning from modernism while at the same time challenging its European dominance.

His response is his work: an approach that combines modernism’s ideals with global cultural representation and references that were “not accepted or regarded as part of the modernist canon.”

Discussions of diversifying the canon cannot be separated from the history of colonization and systemic racism, and indeed Burks’s challenge to the European (and mostly white and male) dominance of design history is also bound up with his identity as an African American.

Of his experience, which includes being the first, and often the only, Black designer to work with many of his European clients, Burks tells hooks, “We, as African Americans, are seen first as Black and seen second as artists or architects or designers.

There’s always that conversation with race that has to be overcome before people understand our work.” He recounts how he has been commissioned by companies that have “literally asked me to make [the product] look African.”

Reflecting on his own career trajectory, Burks identifies a longer road, full of more obstacles, in comparison to his European peers.

Change, he tells Wilkinson, relies on the acknowledgement, understanding, and interrogation of history.

“As Americans, we cannot afford to leave our history behind,” Burks says.

“As African Americans, we must continue to rely on our collective imagination to design new ways of being in community and society with each other as well as our past, present, and future.”

Above all, it is Burks’s process—not the products themselves—that’s truly propositional.

In a world where “so few make design decisions for so many,” Burks writes, one solution is to “involve everyone in the conversation.”

It is a noble ambition, and one that requires comprehensive change to achieve. Perhaps the biggest impact of Burks’s approach, beyond the support of international artisans, will be through films, exhibitions, or publications, such as Shelter in Place.

Objects can tell stories, yes, but typically only if we, as their users or viewers, are willing to do our research to understand what they’re saying.

It will be interesting to see what other avenues of communicating these stories Burks will embrace in future, in order to achieve his seemingly tireless ambition of ushering in a more inclusive, pluralistic future for design.

Burks positions home—the place most of his work is designed for—as the starting point for reshaping society.

In the wake of the Covid-19 pandemic, this is particularly apt; during lockdown, home was, if we were lucky, one of the few places where we could make change.

These days, more people see home as a key arena for expressing our values and ambitions for the future—whether that’s democratic design, social equity, collaboration through craft, or unbounded creativity.

The next step is to take this appetite for change beyond the domestic sphere.

The book Stephen Burks: Shelter in Place will be the focus of the February 18 meeting of the New York Architecture + Design Book Club, a quarterly event series co-organized by Untapped and the Brooklyn bookshop Head Hi.

Burks, along with the artist and writer Christian Nyampeta, will lead the program’s interactive discussion.

Milan Furniture Fair

April 17, 2023New Kida dining chair to be presented during 2023 Milan furniture fair

Living Corriere Della Sera No. 4

Creative Survival Tactics: At Home with Malika Leiper & Stephen Burks by Olivia Fincato

"We transformed a former bakery into a modernist gallery."

By Dennis Scully & Fred Nicolaus for Business of Home

January 23, 2023Stephen Burks wants to open the doors of the design industry.

Disegno Journal

February 15, 2021With the romanticism of a wiser woman looking back on a fleeting youth, Joan Didion once described New York City as the “shining and perishable dream itself”.

By Malika Leiper for Disegno #34 x Het Nieuwe Instituut Design Drafts #1

September 21, 2022How to begin writing about design if the word does not even exist?

By Stephen Burks for the Oak issue of Material Intelligence online, edited by Glenn Adamson.

June 2, 2022Yes, the mighty oak tree, the stuff of legends, is also the traditional

basket maker’s wood of choice in Appalachia, as elsewhere

in the eastern United States.

Stephen Burks: Shelter in Place Book Review in Untapped Journal by Francesca Perry

February 13, 2023The book Shelter in Place considers the possibilities, and the precedents, of the designer’s inclusive approach to creating objects for the home.

Berea College Student Craft

September 26, 2019Today, Student Craft is no longer just a factory of student labor, as it had been for nearly 100 years, but is transforming into an academic program producing open-ended products.

The New York Times by Lauren Messman

April 15, 2024You can always see where you would like to sit at the annual festival of furnishings and household objects.

By Diana Budds for New York Magazine

November 7, 2023Stephen Burks Wants to Finish a 20-Year-Old Conversation With Fran Lebowitz.

Stephen Burks for Goodee

September 1, 2019"I found myself back in school in the midst of a year-long fellowship, where I met Malika."

Najha Zigbi-Johnson for Volume Gallery

September 8, 2023Within this spiritual and cultural context, I engage and understand the most recent work of industrial designer Stephen Burks, who has created a collection of modern altars entitled Spirit Houses.

Perez Projects Presents BD Barcelona: A New Perspective, 50 Years of Design

April 16, 2023By Vasia Rigou for The Chicago Reader

September 19, 2023The Volume Gallery exhibition connects past, present, and future through reverent design.

About

Stephen Burks Man Made is a hands-on collaborative design studio deeply invested in the transformative power of craft techniques that challenge the limits of new technologies within industrial production.

We believe in a pluralistic vision of design that is inclusive of all cultural perspectives and backgrounds.

We bring the hand to industry through a community-driven, workshop-based practice.

Our projects include furniture, lighting, interiors, exhibitions, and product design.

We are Stephen Burks (Principal), Malika Leiper (Cultural Director), Vara Yang (Design Consultant), and Fridolin Jeger (Design Assistant).

Our solo exhibition Stephen Burks: Shelter in Place, formerly at the High Museum of Art in Atlanta (September 16, 2022 - March 5, 2023) is part acclaimed mid-career survey and part commissioned speculative project presenting the last decade of professional practice alongside new expressions of radical domesticity through handcrafted industrial design.

Most recently, Stephen Burks: Spirit Houses opened at Volume Gallery in Chicago and Stephen Burks: Shelter in Place (November 19. 2023 - April 16, 2024) opened at the Philadelphia Museum of Art where Stephen became the first African American to receive the Collab Design Excellence Award.

Follow us on Instagram @stephenburksmanmade and contact us at info@stephenburksmanmade.com.

Stephen Burks

Chicago native, Stephen Burks is an industrial designer, product development consultant, and educator whose innovative approach to design synthesizes craft, community, and industry. Independently and through association with various non-profits, he has collaborated with artisans and craftspeople in over ten countries on six continents. His socially engaged practice seeks to broaden the limits of design consciousness by challenging who benefits from and participates in contemporary design.

Stephen and his studio, Stephen Burks Man Made, have been commissioned by many of the world’s leading design-driven brands to develop collections that engage hand production as a strategy for innovation to express a more pluralistic vision of design including BD Barcelona, Cappellini, Dedon, MASS Design Group, Missoni, & Roche Bobois.

He has had solo exhibitions and led curatorial projects at the Studio Museum in Harlem (Stephen Burks Man Made, 2011), the Museum of Art & Design (Stephen Burks, Are You a Hybrid, 2011), and the High Museum of Art (Stephen Burks: Shelter in Place, 2022).

He has been visiting faculty and a strategic consultant to academic institutions around the globe and taught architecture and design at Berea College, Columbia University GSAPP, ECAL, the University of Arkansas Fay Jones School of Architecture & Design, and the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.

Stephen is the only African-American to win the Smithsonian Cooper Hewitt National Design Award in Product Design and the only industrial designer to be awarded the prestigious Loeb Fellowship at the Harvard Graduate School of Design.

Malika Leiper

Originally from Cambodia, Malika Leiper is interested in the culture of design across various disciplines with a particular focus on emergent contexts in Southeast Asia.

After completing her master’s in urban planning at Harvard’s Graduate School of Design, she consulted with restaurants, non-profits, local governments, and museums on research and strategies to build creative cultural capacity, often through public programming and community engagement.

She approaches design as a collaborative process of translating knowledge and insights from different worlds into one common language through technical, moral and utopian applications.

Most recently, Malika has contributed to Disegno Journal #34 as a Het Nieuwe Instituut inaugural emerging writing fellow with her first published short story, When The Words Don't Exist.

Vara Yang

Vara Yang joined Stephen Burks Man Made as an industrial designer in New York in 2017.

Before working at Stephen Burks Man Made, she worked with several startups helping them bring their products and services to the market, including smart home devices, smartwatches, smart jewelry, and 3D printers.

Now an independent consultant based in Rotterdam, she continues to work with the studio on projects at various scales from furniture design to packaging to exhibitions.

Vara received her bachelor’s in design engineering from National Cheng Kung University in Taiwan and her master’s in Industrial Design from the Rhode Island School of Design.

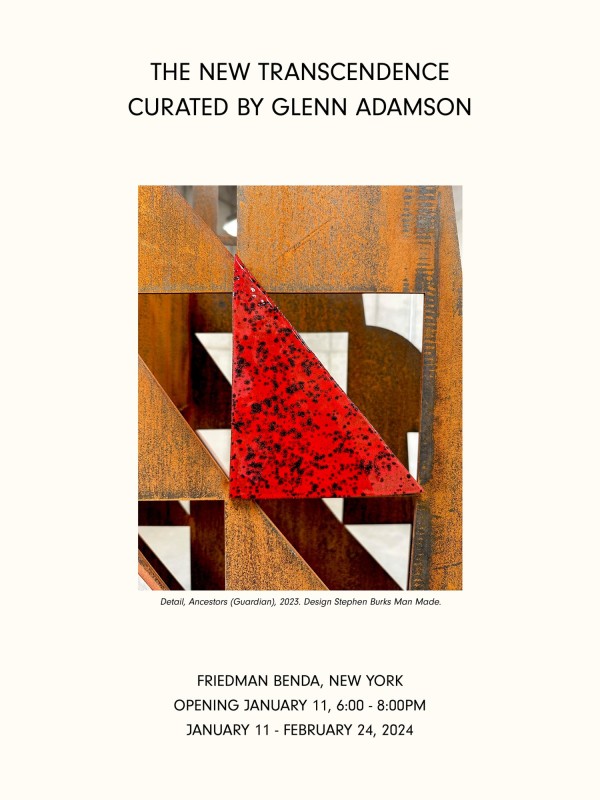

- 2023 Ancestors (Guardian) Friedman Benda

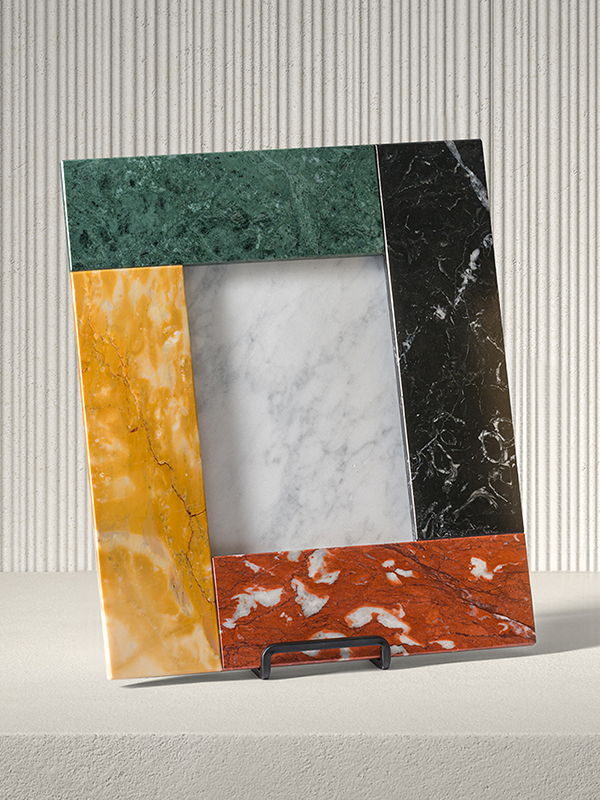

- 2023 Precioso Salvatori

- 2023 Spirit Houses Volume Gallery

- 2023 On New Cosmologies: Stephen Burks Approaches the Sacred Najha Zigbi-Johnson for Volume Gallery

- 2023 The Sacred and Profound By Vasia Rigou for The Chicago Reader

- 2022 Shelter in Place Prototypes High Museum of Art, Atlanta

- 2023 Kida Dining Chair Dedon

- 2023 A Casa Di Burks Living Corriere Della Sera No. 4 Creative Survival Tactics: At Home with Malika Leiper & Stephen Burks by Olivia Fincato

- 2023 BD Barcelona 50th Features Grasso Perez Projects Presents BD Barcelona: A New Perspective, 50 Years of Design

- 2023 Zenith Stephen Burks Man Made

- 2018 Grasso Ceramics BD Barcelona

- 2020 Kida Dedon

- 2019 Kida in Production Dedon

- 2023 Business of Home Podcast By Dennis Scully & Fred Nicolaus for Business of Home

- 2018 Grasso BD Barcelona

- 2008 Horizon Tod's

- 2017 The Others Dedon

- 2019 Islands Living Divani

- 2019 Home as Project Stephen Burks for Goodee

- 2021 Welcome to Contemporaries Disegno Journal

- 2012 Dala Dedon

- 2013 Anwar Parachilna

- 2022 When The Words Don't Exist By Malika Leiper for Disegno #34 x Het Nieuwe Instituut Design Drafts #1

- 2023 Curbed 21 Questions By Diana Budds for New York Magazine

- 2021 Anywhere Kitchen USM Modular Furniture

- 2022 The Making of the Community Basket By Stephen Burks for the Oak issue of Material Intelligence online, edited by Glenn Adamson.

- 2021 Friends & Neighbors Salvatori

- 2023 How Stephen Burks “Future-Proofs” Craft Stephen Burks: Shelter in Place Book Review in Untapped Journal by Francesca Perry

- 2019 The Crafting Diversity Initiative Berea College Student Craft

- 2020 Pixel Blanket Berea College Student Craft

- 2020 Community Basket Berea College Student Craft

- 2013 Variations Calligaris + P:S

- 2015 Ahnda Dedon

- 2014 The Traveler Roche Bobois

- 2023 Shelter In Place The High Museum of Art

- 2022 The Spruce Berea College Student Craft

- 2004 Missoni Mogu Fun Fun Missoni

- 2011 Are You A Hybrid? Museum of Arts & Design

- 2020 Making of Broom Thing Berea College Student Craft

- 2014 A Free Man The White Briefs

- 2015 Frame Calligaris

- 2018 Floats Bolon x BD Barcelona

- 2022 Stephen Burks: Shelter In Place Catalogue By Monica Obniski for High Museum of Art

- 2016 The Traveler Outdoor Roche Bobois

- 2023 Dedon Launches Kida Dining Chair Milan Furniture Fair

- 2017 Irregular Weaving A/D/O

- 2011 Roping Dedar Milano

- 2011 Stephen Burks: Man Made Studio Museum of Harlem

- 2013 Hidden Gem Harry Winston

- 2018 Trypta Luceplan

- 2020 Broom Thing Berea College Student Craft

- 2015 Senegalese Basket Workshop

- 2013 Variations Workshop Journal Calligaris & P:S

- 2021 Magniberg Magniberg & Caroline Tompkins

- 2023 Powerhouse Ceramics Design Fellowship Friedman Benda Gallery

- 2024 Clay Break University of Arkansas Art Ceramics Department

- 2018 BD x Bolon Workshop BD Barcelona & Bolon

- 2024 Taking a Moment to Lounge at Milan Design Week The New York Times by Lauren Messman